Last week, he said, "We will return American astronauts to the moon, not only to leave behind footprints and flags, but to build the foundation we need to send Americans to Mars and beyond.” Waiting in the wings of this new space race are scientists. It’s imperative from a historical point of view.” "I could not imagine if China was dominating space. “We just should not be absent from space," says Schmitt. Today, he believes China could gain an edge in developing lunar resources if the US government doesn't push for a greater presence on the lunar landscape. “The situation now is not unlike the Apollo days,” he says, when the US was locked in a Cold War over technological and military dominance with the Soviet Union. “Space is geopolitical and it’s important for the United States to be there,” Schmitt said in an interview at the LEAG conference. What’s changed is our interest in going there.” And while the federal moonshot is still just a plan, Green is reviewing proposals from scientists who want to put experiments on upcoming commercial rockets.īut Harrison Schmitt, a former astronaut and geologist on the final Apollo 17 mission in 1972, feels differently.

“The moon has been important planetary science since day one, that hasn’t changed. “The moon has the history and evolution of our solar system written on its surface, if we can get there,” says Jim Green, NASA director of planetary science. “Now we want to go back and sample these ancient terrains," says Needham.Īlready, NASA is working with scientists to fulfill their lunar ambitions. They want to know what kind of material might still be there from the early days of the solar system. NASA scientists are also interested in the South Pole-Aitken Basin, which is the moon's biggest and oldest impact crater. Needham and others believe there may be areas there that have ice, for example. Proving it, for Needham and her colleagues, means going to places on the moon that were never explored by the Apollo astronauts in the 1960s and 1970s-including the far side of the moon where radio communication with Earth is more difficult.

“I’m saying that it happened,” Needham says. Building on Earthly observations of gas-releasing lavas, her work suggests that the moon's atmosphere could have formed when surface volcanoes belched out gases that settled onto pockets of cooling rock-a volcanic smog that may have lasted 70 million years before dissipating.

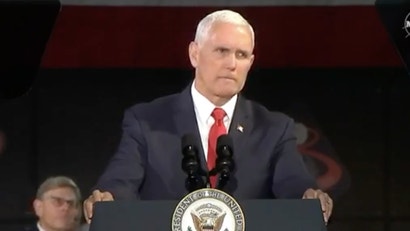

Needham studies how volcanic activity formed the rocky bodies-Mercury, Venus, Mars, Earth, and the moon-and this month she published a paper hypothesizing that the moon may have had a hazy atmosphere. “I’m excited to get boots back on the ground,” says Debra Needham, a planetary scientist at the Marshall Space Flight Center. And these days, they're about as giddy as lunar scientists can get. These scientists hope to piggyback onto any future US moonshot so they can answer questions about the origin of the solar system, as well as test the kind of experiments they hope to run on Mars. Pence didn’t give a date, details, or even a ballpark cost during his speech at the opening of the National Space Council.īut he did give a morale boost to 200 attendees (a record) at NASA’s Lunar Exploration Advisory Group, which held its annual meeting this week in Columbia, Md. At the beginning of the month, Vice President Mike Pence announced that the US, at long last, will go back to the moon.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)